By Annabelle Lee

MALAYSIANS KINI | Nazir Harith Fadzilah was studying engineering in Melbourne, Australia when he fell hard for secondhand bookshops. It was in Australia that he stumbled upon a book of Malay poems which would set him on his mission.

Returning to his hometown of Ipoh last year after six years abroad, the 29-year-old got straight to founding Tintabudi, a secondhand bookshop where he sells books on literature, philosophy and art as well as an impressive selection of Malay literature.

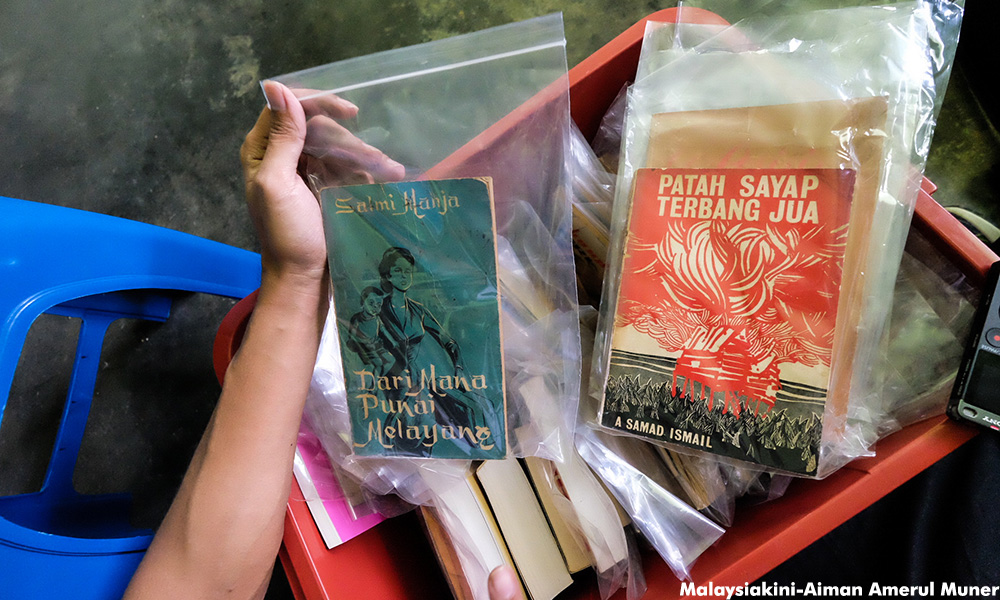

“This is the first edition of A Samad Said’s ‘Salina’, which was published in 1961,” he said, squatting over a box of books, all kept in individual plastic ziplock bags.

Tintabudi – tinta means ink in Bahasa Malaysia while budi means kindness – is a humble operation.

Most are rare editions which he tries to keep in mint condition. Samad’s books reside at Tintabudi alongside those from other National Laureates like Usman Awang and Shahnon Ahmad, Malay literature giants Za’aba and Latiff Mohiddin as well as rare copies of the works of Salmi Manja.

“Salmi stopped writing in the 1970s after marrying A Samad Said, so it’s hard to come across her books, but I have some,” Nazir shared.

The search for the seminal works has not been easy.

Despite narrowing his search to only modern text from circa 1950, Nazir said very little of these works are available in digital format while physical libraries have been guilty of discarding the books.

“It was important to me to have even just a small bookshop. Not just as a distribution point for good books but also as an alternative space where people could come in and talk about books.

“When you look at our reading and political climate, (you could see that) it really needs to be done. I was convinced it would work because there are a lot of people who read but the problem is the access to materials.

“I really wanted to ignite a culture of thinking, reading people,” he said.

Nazir said that lack of access to good Malay literature have left many to conclude the language lacked depth and sophistication – a misconception he fights against one book at a time.

This is Nazir’s story in his own words:

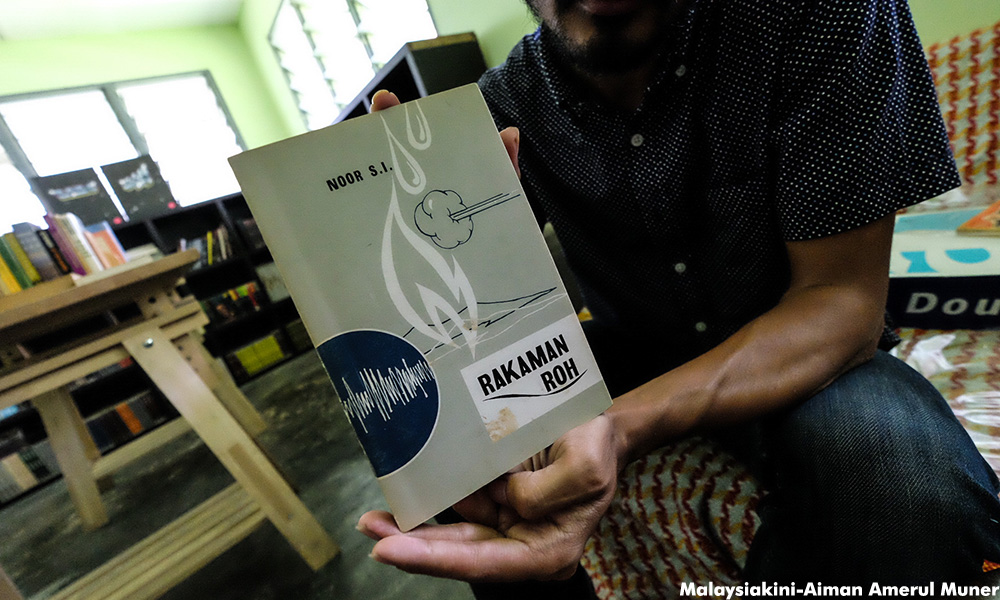

MY INTEREST IN MALAY LITERATURE BEGAN after reading ‘Rakaman Roh’ (Soul Recordings) by Malaysian poet Noor SI. I began to wonder why there was so much I didn’t know about Malay literature.

I bought the book in this bookshop in Canberra, that sold Malay books. Prior to this, I had never even heard of Noor SI. I became fascinated by his poetry and the best part was the book included hand-scribbled annotations by the previous owner of the book – an Australian professor named C Skiner who taught Malay at a university in Canberra.

After reading that book I started looking for similar books in Malaysia, online and through friends back home.

IT WAS FRUSTRATING to search for Malay books from Melbourne because there was no online access to our own Malaysian materials.

There is an abundance of materials on the history of Australia or on the American Revolution, but when it comes to Malay literature or Malay historical writing, these are really hard to come by.

Our institutions like the National Library, the National Archives and Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka (DBP) have not done the work of transferring them to a digital medium.

IT IS HARD TO FIND BOOKS LIKE THESE EVEN IN MALAYSIA. Or if you find them, and they’re in bad condition.

You could perhaps find these books in our libraries, but some of our libraries even discard these books!

I was fortunate enough to have met people who wanted to sell their stuff and who told me about people selling these books. I met this one pak cik who had a collection of original handwritten letters by Sir Richard Olaf Winstedt (1878-1966).

He said they were discarded by a library. Winstedt was an English colonial administrator and Orientalist specialising in British Malaya. These letters really are monumental historical documents.

With the millions of ringgit at their disposal, it’s sad that our institutions don’t have that urgency or stringency to preserve these materials.

WHEN I DID MY SECOND EXHIBITION at APW in Bangsar, Kuala Lumpur last November, I met with a lot of urban Malaysians who were surprised by how abundant Malay literary materials are.

Some of them knew the names of the authors but they were quite surprised to actually see the materials. And with a couple of books, they didn’t even know these existed! Even Mohd Salleh, one of our own National Laureates, was surprised to see Shahnon Ahmad’s ‘Srengenge’ at my booth.

I HAVE BOOKS BY THE ASAS ‘50 BUNCH – Ashraf, A Samad Ismail and A Samad Said. They were a group of left-leaning writers active in the 1940s-1960s – before and after Merdeka.

Many of them were journalists and wrote a lot in newspapers and magazines, so they did a lot of socially conscious writing.

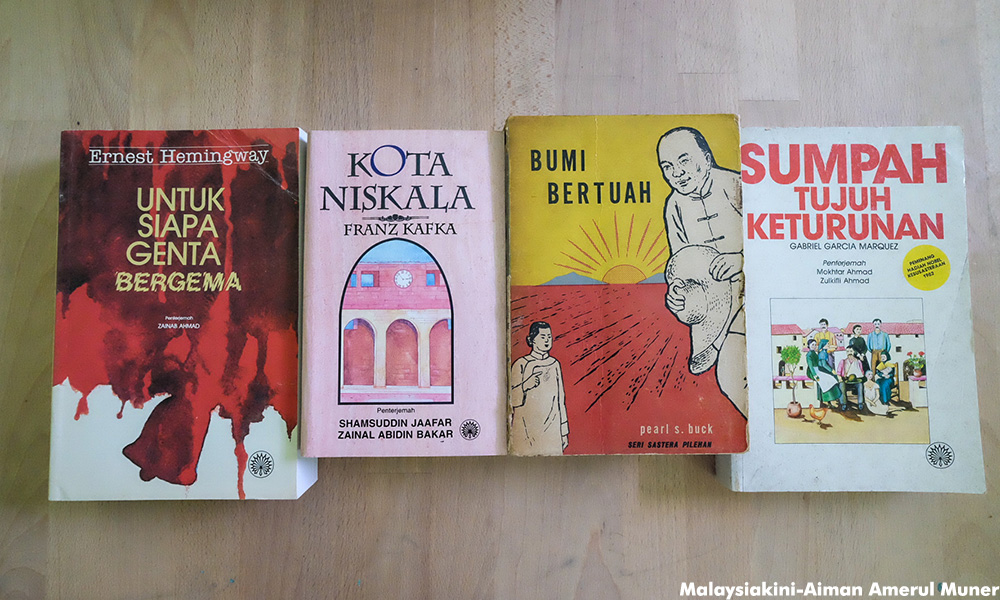

These writers translated a lot of seminal Western literature to Rumi (romanised Malay), to make them accessible to the Malay-speaking world.

I have a few good Malay translations, not just direct translations but ones that took into account the cultural differences – Ernest Hemingway’s ‘The Old Man and the Sea’, Joseph Conrad’s ‘Gaspar Ruiz’ and works by John Steinbeck and Franz Kafka.

I have some books by Faisal Tehrani as well, including one of his earliest novels from the 1990s – ‘Cinta Hari-hari Rusuhan’ (Love In the Days of Rioting).

I’ve realised a transition of Malay literature production, from the socially aware work in the 60s-70s to the 90s when you see more pop-fiction and romance kind of stuff.

DR MAHATHIR MOHAMAD might have had a part to play by developing Malaysia to focus more on hard sciences, and less on the social sciences.

The publishing environment created by the Printing Presses and Publications Act 1984 has also contributed to Malay literature becoming a lot less critical.

PEOPLE TEND TO THINK YOU CAN’T HAVE THESE SOPHISTICATED DISCUSSIONS IN MALAY LANGUAGE because our language is not up for it, which is crazy! I think we have this belief because we have not read our past writers.

I also think our lack of contact with diverse and complex literary works in Malay sometimes make us misjudge the depth of the Malay language, and perhaps even the culture.

Before I started, I saw how chain bookshops in Malaysia were selling pretty mainstream books,and when DBP shops in different states started closing down one by one, a lot of people lost access to good books.

IT WAS IMPORTANT TO ME to have even just a small bookshop. Not just as a distribution point for good books but also as an alternative space where people could come in and talk about books.

When you look at our reading and political climate, it really needed to be done. I was convinced it would work because there are a lot of people who read but the problem is the access to materials.

I really wanted to ignite a culture of thinking, reading people.

I WANTED A NAME that encapsulated what I was trying to do, a name related to literature and to the human soul.

‘Tinta’ is an old world for ‘dakwat’, which means ink in Malay. I was really drawn to the word ‘budi’ because it’s an interesting Malay word. It encapsulates our heart, mind, actions, language and how we speak.

Put together, ‘Tintabudi’ illustrates how the human condition, encapsulating the heart, mind and soul, can be poured into written form. And that’s basically what literature is.

IT’S COMMON to assess a country’s reading habits by looking at book sales data. But there are so many intricacies of reading culture that are outside the circumference of data collection mechanisms.

I want to record the reading experiences of normal Malaysians to have a better understanding of our reading culture.

(This is why) I’m working on a video documentary called #CeritaPembaca (Readers’ Stories) that looks at what books ordinary Malaysians are reading, and their reading habits.

I TRY TO DOCUMENT OUR HERITAGE by collecting literary magazines like Dewan Sastera and Dewan Bahasa. These magazines have a particular currency which I appreciate.

IN THE END, IT’S UP TO THE GRASSROOTS to do it, ordinary people who are passionate about books need to do it.

MALAYSIANS KINI is a series on Malaysians you should know.