By Annabelle Lee & Syazwana Amir

CORONAVIRUS | Businesses have ground to a halt as a result of the movement control order and this has decimated the livelihoods of the refugee workforce.

At a block of low-cost flats in Cheras, a third of families hail from the embattled Chin State in Myanmar.

Since the order came into force on Wednesday, many have been unable to head out to their usual jobs in restaurants, cleaning services, agriculture and construction.

The irregular nature of their employment means that there are no contracts, monthly salaries or paid leaves. They are only paid if they show up to work, and often at a lower rate than citizens.

Sang Bik, who runs a refugee school on the ground floor of the block, tells Malaysiakini that many of his compatriots are in distress.

“Some of the families have started to ask me – how can I manage to pay for rental? I have no job. I have no income for food and drinks for the children.

“How do they do this? They don’t know, they have no idea,” he relayed through his face mask.

His school has also been affected.

Usually bustling with almost 90 students, classes are off due to the order.

The school’s operations are supported by monthly fees, but he expects that most parents will not be able to afford it since they are now without any income.

“If they can’t pay fees for the children, we can’t pay the rent for the school. This is all connected […]

“Even if the school is closed, we still have to pay the rent,” Sang (above) explained.

He furrowed his brow at the thought of the Covid-19 outbreak worsening and a further extension of the order period.

Will they treat us the same?

Earlier, Malaysiakini observed as he turned the school into a distribution centre for 50 food packs prepared by local social enterprise PichaEats.

Ringing up the parents of his students, he told them to come one family at a time to prevent queues and reduce the risk of Covid-19 contagion.

Many walked down from their apartments wearing masks and collected the food shyly before heading right back into their units.

A vulnerable community with no access to subsidised healthcare, Sang wondered if refugees would receive an equal level of medical attention as citizens should any of them contract the highly infectious virus.

“Will the government spare some room to give treatment for us?” he asked.

Malaysia does not officially recognise refugees and regards them as undocumented migrants.

This is despite being home to some 178,990 refugees and asylum seekers, according to the UNHCR.

Need help sponsoring meals

For a catering service like PichaEats, event cancellations due to the Covid-19 outbreak have caused sales to shrink two-thirds.

The enterprise delivers food cooked by refugee chefs, with whom it splits its profits. It also routinely donates food to needy groups as a community service initiative.

Business is down, affecting both the chefs and company, but the need for food has spiked during the movement control order period.

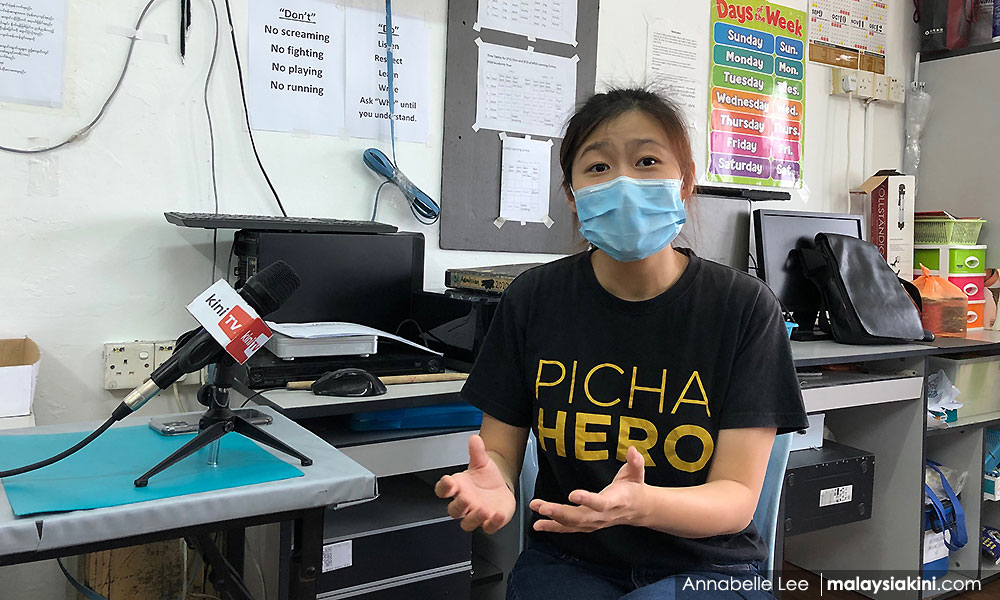

Interviewed after distributing the food packs to the refugees, PichaEats co-founder and marketing director Suzanne Ling (above) shared that stranded university students from the B40 group and frontline healthcare workers have also reached out for food.

To cope with this, the company is appealing to the public for funds to enable it to give free meals to these groups over the next two weeks.

“This will have multiple impacts. It impacts the community that needs food and also the community who is cooking the food (the refugee chefs).

“It also keeps this business afloat, we have a full-time team of 10 people who are all drawing a salary,” she told Malaysiakini.

PichaEats is accepting any amount of financial sponsorship for its free meal initiative and interested parties can contribute to its Maybank account (Account number: 564146643727)

Contributions need to be labelled “Zaza Movement” and transaction receipts can be sent to 012 6794 353.

The initiative is named after a late refugee chef-partner whose dying wish was to give out free meals to those in need.